On This Day: Birth of Isabella of Valois

Posted on

On this day in 1389 Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France, gave birth to a baby girl in Paris. Princess Isabella was the third child and second daughter of the Queen and her husband King Charles VI. Sadly she did not have the best childhood, or the longest life.

Childhood

Isabella's parent's marriage had originally seemed like it was divinely blessed. Charles reportedly fell in love with his bride at first sight, and showered her with gifts and a lavish coronation. Their first child was a boy named Charles, who died aged eight, followed by Jeanne and then Isabella.

But things slowly took the shine off the royal life. Charles developed a mental illness, which first appeared in 1392 when Isabella was three years old. For the rest of his life Charles would swing between lucidity and insanity, a situation that led to various political players attempting to gain control of the country. One of those players was Isabeau, who quickly developed a reputation in the medieval chronicles for neglecting her children.

Charles' periods of sanity meant that Isabeau continued to fall pregnant, in total Isabella was followed by nine siblings. The Royal nursery was reportedly far from what it should have been, records stated that the children were left to run around in old, dirty clothes, and that if it wasn't for the servants they would have starved, as Isabeau never bothered to arrange supplies. Modern historians have pointed out that the actual records from the court show payments made for toys and clothes for the children, suggesting that even if Isabeau didn't spend much time with them, she certainly didn't neglect them.

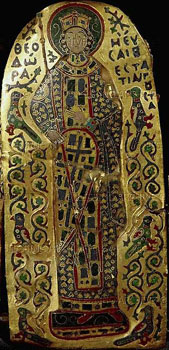

Charles' illness also meant that France was vulnerable to attack from outside as well. France and England had been at war for years, but it was a fight that was proving to be increasingly unpopular in England, and in the end Charles and King Richard II negotiated a truce, with Isabella playing a key part. Richard was a widower, his wife Anne of Bohemia died in 1394, and he had no children. The peace with France was sealed with a marriage to Isabella, who was a mere seven years old when the wedding took place in October 1396.

England

After the wedding Isabella was taken over the English Channel and deposited safely in the care of two English duchesses and provided with a governess from France. Richard reportedly visited her frequently, when he would take her for walks in the garden. Despite the wealth that she brought with her, she was far from popular with English public or Richard's court, who felt that he should have married a woman old enough to bear children.

Despite the unconventional home set-up, Isabella appears to have had genuine affection for her "husband". After Richard was deposed by his cousin Henry, the new king decided that the French truce could continue. He had a son, also called Henry, who was closer in age to Isabella, and by marrying his heir she would still eventually be Queen of England. Isabella on the other hand appears to have refused, and went in to official mourning for her husband. After a certain amount of negotiation (Henry was probably stalling in the hope that Isabella would change her mind), she was allowed to return to France with the jewels and other goods that her family had given her for her wedding.

In June 1406 at the age of fifteen Isabella married for a second time, to her cousin the Duke of Orleans. Four years later she gave birth to her only child, a daughter named Joan, and passed away a few hours later. In her time as Queen of England she had little opportunity to make her mark, and her early death meant that she left little impression on French politics. Her younger sister Catherine went on to take her throne, marrying Henry V in attempt to bind France and England together once more.

often raised an eyebrow over the way their raised their children. While it was common for high-born children to be fostered out to other noble families for their education, the Royal couple seem to have been more distant than was usual. However, Alphonso was their ninth children (out of a potential sixteen in the end), only three survived to see their new brother, and as mentioned Henry died eleven months after Alphonso's birth. It might be that Edward and Eleanor, rocked by so many deaths, needed to keep an emotional distance.

often raised an eyebrow over the way their raised their children. While it was common for high-born children to be fostered out to other noble families for their education, the Royal couple seem to have been more distant than was usual. However, Alphonso was their ninth children (out of a potential sixteen in the end), only three survived to see their new brother, and as mentioned Henry died eleven months after Alphonso's birth. It might be that Edward and Eleanor, rocked by so many deaths, needed to keep an emotional distance.