On This Day: Death of Maria Theresa of Spain

Posted on

"This is the first trouble she has ever given me."

As Maria Theresa lay dying, her husband's words showed the kind of Queen of France that she had been. Quiet, unassuming, supportive to her husband, and loving to their children. King Louis XIV could not have found a better definition of her time with him.

Princess of Spain

Maria Theresa was born in September 1638 the daughter of King Philip IV of Spain and his wife Elisabeth of France. France and Spain had been closely connected by marriage in the previous generation, her parents were the siblings of the King and Queen of France, as King Philip's sister Anne had married Queen Elisabeth's brother Louis. Like many such marriages between France and Spain, the weddings had been decided upon in an attempt to bring peace between the two countries, unfortunately it didn't work.

She grew up in the strict formality of the Spanish court, which encouraged solemnity and serious pasttimes. Her mother died when she was just six years old, and her father remarried several years later. Maria Theresa does not appear to have got on well with her new step-mother, and so may have lacked the kind of warm, affectionate home that her future husband had.

Queen of France

After many years of war a peace deal was brokered between Spain and France, and was to be sealed with a marriage between Maria Theresa and Louis XIV. They were the same age, in fact there were only a few days age difference between them, and the marriage had been hoped for for many years by Louis' mother Anne. Any potential courting between the afianced couple was stifled by Maria Theresa's father, who refused to let his daughter even read a letter from her future groom, and who strictly supervised their first meeting shortly before the wedding (in fact he banned Louis from even being in the same room as Maria Theresa, an order that the King of France tried to evade by lingering in the doorway while his brother chatted to the princess, King Philip continually refused to allow him in to the room).

It's reported that on their wedding night, Maria Theresa made her husband promise to never spend a night sleeping away from her. Whether or not this was true, it certainly was a habit that Louis stuck to, although it wasn't enough to prevent him having many affairs through their marriage. His wife found herself settling in to her new home, with help from her aunt, who was thrilled to have another Spainiard at court. There was no bickering between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law, instead the pair of them frequently prayed and visited convents together.

In fact Maria Theresa was a little too Spanish for the French court. Her new home was one that loved innovation, fashion, dancing and wit. Her upbringing had left her rather shy, she preferred to keep to herself with a select group of companions, and she wasn't fashionable or quick enough to be a leader of the court. Despite this, she was a good Queen to Louis. She was upset by his frequent affairs, but realised there was nothing she could do to stop them. She even sponsored one of her husband's former mistresses, Louise de la Valliere, when she decided to retire from court and become a nun. Louis in turn protected her from any disrespect on the part of his other women, rebuking them when they declined to show her the deference required by her position. For over ten years her main rival was Athenais de Montespan, whose disrespect as well as her place by the King's side infuriated Maria Theresa.

If royal marriages were designed to create peace and provide an heir, then Maria Theresa failed in the first part, France and Spain were still consistently at war over the years. But in the second part she succeeded, as she gave birth to six children, of whom three were sons. The first, also called Louis, was born on 1st November 1661. Sadly it was only this eldest child who would outlive her, her eldest surviving daughter lived for five years, and her other children mostly died within weeks of birth.

Maria Theresa's own death would come as a surprise, as her illness was sudden, and her decline swift. She reporedtly surprised the court by never complaining about the agonising treatments she went through, medical intervention still didn't include any pain relief. She died on 30th July 1683, leaving her husband to utter the simple, but evocative, summation of their life together.

Interested in biographies of Royal women? You might like my Unlucky Princess blog series.

Fan of King Louis XIV? He has a badge!

her son before an older relative could claim it, she was not allowed to exercise the powers of a regent. Instead she too left her son in favour of her home country, returning to Picardy when Alexander was ten. Like Isabella of Angouleme she took a second husband, but unlike Isabella she had no children with her second husband, sparing Alexander the kind of political envy that Henry's half-siblings caused years later.

her son before an older relative could claim it, she was not allowed to exercise the powers of a regent. Instead she too left her son in favour of her home country, returning to Picardy when Alexander was ten. Like Isabella of Angouleme she took a second husband, but unlike Isabella she had no children with her second husband, sparing Alexander the kind of political envy that Henry's half-siblings caused years later.

where she earned high praise for both her attitude and abilities. She was then parachuted in to France, where she met up with a local network. Her role was to oversee the groups finances and handle the division of weapons and supplies dropped by the Allies, but she was soon helping recruit new members, plan and oversee operations, and eventually came to lead over 7000 men. She claimed that her greatest moment was cycling a 300 mile round trip to get new wireless codes. She also killed a German sentry to prevent him raising the alarm, and shot a woman who was a German spy. In total her team killed around 1400 Germans, while suffering only 100 casualties.

where she earned high praise for both her attitude and abilities. She was then parachuted in to France, where she met up with a local network. Her role was to oversee the groups finances and handle the division of weapons and supplies dropped by the Allies, but she was soon helping recruit new members, plan and oversee operations, and eventually came to lead over 7000 men. She claimed that her greatest moment was cycling a 300 mile round trip to get new wireless codes. She also killed a German sentry to prevent him raising the alarm, and shot a woman who was a German spy. In total her team killed around 1400 Germans, while suffering only 100 casualties. Amelia, Alice Maud, James Henry and Kate Harris (my great-grandmother) all ahead of him, and Albert Edward, Harry and May still to follow over the years.

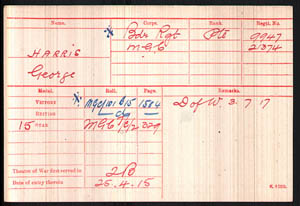

Amelia, Alice Maud, James Henry and Kate Harris (my great-grandmother) all ahead of him, and Albert Edward, Harry and May still to follow over the years. with them. They were promptly shipped back to the UK, and after a few months training were ready for deployment. But a lack of surviving service record hasn't stopped me from piecing together some of George's First World War history. His medal card shows that his first "theatre of war" was "2B", army shorthand for "Gallipoli", and that he first entered the war on 25th April 1915. On that date, 25

with them. They were promptly shipped back to the UK, and after a few months training were ready for deployment. But a lack of surviving service record hasn't stopped me from piecing together some of George's First World War history. His medal card shows that his first "theatre of war" was "2B", army shorthand for "Gallipoli", and that he first entered the war on 25th April 1915. On that date, 25

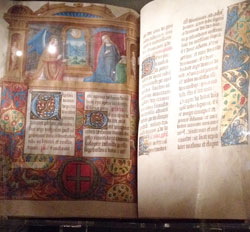

the Crown. However in the 1800s the Order was reformed as a chivalric order, with a new hospitaller organisation created thirty years later. The Order founded a series ambulances, aptly named "St John's Ambulance", which were designed to give members of the public lessons in first aid. The rapid industrialisation in Great Britain had not been accompanied by an increase in helping people work safely, and certain industries such as railways and mines often had high casualty rates. By offering first aid to workers and the public, it was hoped that someone who had been injured could be kept alive long enough to be taken to hospital or seen by the local doctor. It's from this that the modern St John's Ambulance organisation grew.

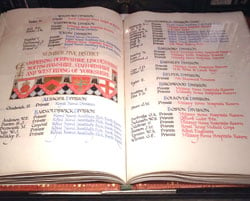

the Crown. However in the 1800s the Order was reformed as a chivalric order, with a new hospitaller organisation created thirty years later. The Order founded a series ambulances, aptly named "St John's Ambulance", which were designed to give members of the public lessons in first aid. The rapid industrialisation in Great Britain had not been accompanied by an increase in helping people work safely, and certain industries such as railways and mines often had high casualty rates. By offering first aid to workers and the public, it was hoped that someone who had been injured could be kept alive long enough to be taken to hospital or seen by the local doctor. It's from this that the modern St John's Ambulance organisation grew. "Roll of Honour" of members who died in the First World War, and more information about the first aid work of the modern St John's Ambulances, including it's work at the eye hospital in Jerusalem and training people in first aid in Africa.

"Roll of Honour" of members who died in the First World War, and more information about the first aid work of the modern St John's Ambulances, including it's work at the eye hospital in Jerusalem and training people in first aid in Africa. Isabella of Bourbon. Her mother died in 1465, leaving Charles with Mary as his only heir. The general view at the time was that a girl couldn't possibly rule, and therefore Charles decided to remarry. In 1468 Mary acquired a step-mother, Margaret of Burgundy, the sister of King Edward IV (and later, Richard III) of England. Margaret and Charles never had a child, but Mary became close to her step-mother, and it was Margaret who guided Mary's steps when tragedy struck again in 1477, when Charles died in the Battle of Nancy.

Isabella of Bourbon. Her mother died in 1465, leaving Charles with Mary as his only heir. The general view at the time was that a girl couldn't possibly rule, and therefore Charles decided to remarry. In 1468 Mary acquired a step-mother, Margaret of Burgundy, the sister of King Edward IV (and later, Richard III) of England. Margaret and Charles never had a child, but Mary became close to her step-mother, and it was Margaret who guided Mary's steps when tragedy struck again in 1477, when Charles died in the Battle of Nancy.