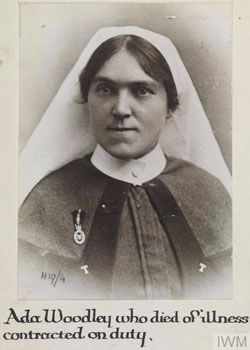

Ada Woodley - First World War Nurse

Posted on

On 10 January 1918, a nurse named Ada Woodley died at Littlebury in Essex. She's not a famous woman in history, but when me and my fiancé stumbled on her grave two years ago while visiting this beautiful old village, I decided to research her. It's rare to find a war memorial grave in a local cemetery, and I'd certainly never seen one dedicated to a woman before. But researching Ada's story reminded me that women who worked hard for their country during the war weren't really treated with the same amount of respect as their male counterparts.

Home in Littlebury

Ada was born around 1886 at Littlebury. Woodley was her mother's maiden name, and as such Ada appears to have been illegitimate. She can be found on the 1891 census living with her mother Sarah, her maternal grandfather George Woodley, and her step-father Daniel Perrin, as well as a 2 month old half sister named Elizabeth. Ada had kept the Woodley name, but obviously I don't know if that was her mother's choice, or if Daniel didn't want her to take his name.

By the 1901 census Ada was out making her own way in the world as a servant for the Pryke family in Saffron Walden. Her employer, Charles Edwin Pryke, is noted as "Superintendent of Police", so Ada may have been working in quite a nice house. Saffron Walden isn't too far away from Littlebury, so she may have been able to return and visit her mother quite frequently. Sarah and Daniel had increased their family, Elizabeth had been joined by Annie, Mabel, Harry and Frederick, and were still living with George Woodley.

Nurse Woodley

In 1911 we first see Ada as a nurse. The census for this year shows her in Dearnley near Rochdale, where she was employed by the workhouse as a hospital nurse. Evidently at some point in those ten years Ada decided that being a servant wasn't the career for her, and made changes in her life that enabled her to train as a nurse and find employment further away from home. The workhouse at Dearnley still stands, with a grand imposing red-brick façade and clock tower. The infirmary, where Ada would have worked, was built in 1902 and appears to be tucked away in the north corner, possibly where it could be better isolated during serious epidemics.

Three years later, war broke out. As it became clear that it wouldn't be "all over by Christmas", more people were expected to show their commitment to war work. In the case of women such as Ada, there was a need for them to work in the military hospitals that had sprung up in both Britain and across Europe. On 21 June 1915 Ada Woodley joined the Territorial Force Nursing Service. Maybe she hoped to be sent abroad, some nurses were sent to work on hospital ships in the Mediterranean, others were dispatched to France and Belgium to serve in casualty clearing stations and hospitals near the coast. But many more were required to stay in Britain, and look after the men who were invalided "back to Blighty". In Ada's case she was sent to the 2nd Western General Hospital in Manchester.

Ada appears to have settled in well at the hospital. The matron in charge of her clearly tried to help fight her corner when she became ill, something she may not have done for a nurse she rated less highly. The TFNS also wrote to her mother after her death stating that "The council have placed on record the cheerful and willing service she rendered to her country, which was so appreciated at the 2nd Western General Hospital".

Illness

The first incidence of serious illness appears in Ada's nursing records in July 1917, when she was granted two months sick leave. At a time when the country was under great strain from the war effort, and injured men were being sent back from the front lines with increasing frequency, 2 months of leave suggests quite a serious illness. She travelled back home to her mother at Littlebury, and sought treatment there. In September 1917 a further two months sick leave was granted, but this is where war time bureaucracy really starts to show it's less helpful side, something that Ada's mother would have to deal with after her death.

A series of letters kept in Ada's file detail the sudden decline in her health. A letter from 14 September, sent to Ada, informs her that she is only eligible to receive three months sick pay as her illness is not caused "in and by" the service. Therefore, despite her sick leave totalling four months up to October, she will only receive three months pay. The letter also informs her that once her four months is close to expiring she'll be required to attend another medical board meeting, presumably to show them that she has recovered.

This letter wasn't what Ada was expecting. There's a gap of a month in the records, but a letter written by Ada herself dated 9 November 1917 appears in her file. In it she defends herself against what's clearly a basic box-ticking exercise, highlighting in her letter that she can't attend the medical board as directed, as she's confined to her bed. She also states that "I refuse to accept this statement" about her work not contributing to her illness. She highlights that when she first joined the TFNS she had a certificate confirming her good health, and in the two years she's worked at Manchester she hasn't had a single day off sick. She also points out that since returning home she's been under medical supervision, which has included being seen by a specialist. The conclusion she's received from her doctors is that even if her illness hasn't been caused by the hospital, then the strain and hard work has helped it develop.

Throughout the record I couldn't see anything indicating what was wrong with her, only that it was serious. At one point a note states that she's being treated by radium, which was used for a number of illnesses at the time. Given her job involved helping injured men, it may be that helping lift those heavier than herself led to a hernia or internal haemorrhage, something that was difficult to treat properly, and which could lead to a serious infection.

Sadly Ada's condition went downhill quite quickly, and it became obvious that she wasn't going to get better any time soon. One letter from her former Matron-in-Chief encourages the War Office to deal with her discharge from the service as quickly as possible as she was seriously ill. The Matron had already tried to help, asking for a medical board to be convened at Ada's home as she was too ill to travel to the necessary meeting. Given that the Matron was still up in Manchester, it's quite likely that she and Ada were keeping up correspondence, checking on how her former colleague was doing and becoming increasingly concerned when she heard about how Ada was being treated.

Ada was finally invalided out of the TFNS on 28 November 1917. This at least meant that she no longer had to worry about being summoned before a medical board to prove she was unfit for work, and probably came as a relief to her and her mother. A gratuity was then paid of just over £24, the letter confirming receipt of the money was written by the Reverend Ernest Edgeley, the vicar of Littlebury. The letter was dated 7 January 1918, Ada died three days later on 10 January. Given that we know from other letters that we was literate, with a lovely clear handwriting, she was clearly too sick to manage this last task herself.

Fighting the War Office

Reverend Edgeley proved to be a good friend to Ada's mother Sarah. The rest of the file contains letters written by the Reverend on Sarah's behalf, it's quite possible that unlike her daughter, her literacy was limited. Sarah had to pay for her daughter's funeral out of the money Ada had left in Sarah's possession. Ada had no will, and the War Office held on to the money for such costs as part of her Estate. Sarah had to apply to the War Office for the funeral expenses to be reimbursed, but the reply from the Office, dated June 1918, refused. "As the deceased was of illegitimate birth Mrs Perrin has no legal claim to the amount due to deceased's estate from Army Funds".

This must have been the last kick in the teeth for Ada's mother. The letter goes on to inform her that if she writes in, stating that if she had supported Ada in her childhood, then they would reconsider her application. Reverend Edgeley became involved again at this point, you can almost hear the anger in his letter; "I can certify from my own knowledge as vicar of the Parish extending over nearly 30 years, that Mrs Perrin supported the deceased during her infancy, childhood, provided her with a home in instances of holiday and finally nursed her through her last illness". Soldiers were encouraged to make their wills before they left for the front line, evidently such legal niceties weren't encouraged for those serving in the services at home, including nurses. Or perhaps Ada's end came too suddenly for it to be a consideration.

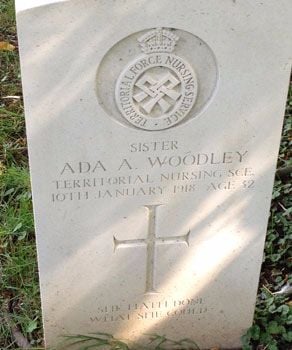

Ada's mother chose the quote she wanted on her daughter's headstone, it simply reads "She hath done what she could".

The picture included is from the Imperial War Museum collection (© IWM (WWC H19-4)), it was submitted to the war museum in 1918 following two letters written by Reverend Edgerley. The grave photo was taken by me.

Add a comment: