On This Day: Eleanor of Aquitaine's Second Wedding

Posted on

You may remember my blog post a few weeks ago about Eleanor of Aquitaine's divorce from King Louis VII of France. Their marriage had been rocky for years, a split was virtually inevitable. Louis tried to ensure that he still had some say in Eleanor's life, by including a clause that stated that she had to ask his permission before remarrying. In this way he hoped to prevent her from allying herself with someone who would pose a danger to his kingdom.

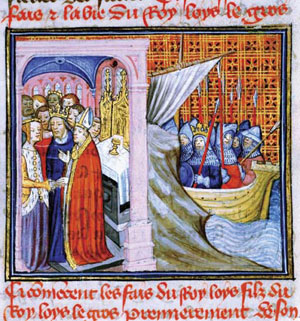

Unfortunately for Louis, on this day, 18th May 1152, remarrying without permission was exactly what Eleanor did. Her groom was none other than Henry "Plantagenet", Duke of Normandy, and their marriage united two of the biggest duchies in France, creating exactly the kind of problem Louis wanted to avoid.

Henry Plantagenet

The young groom, who was nine years younger than the bride, was the son of Duke Geoffrey of Anjou and his wife the Empress Matilda, a princess of England by birth and technically the rightful heir to the English throne (once you got past her gender). This was another rocky marriage, but unlike Eleanor it wasn't one that would be put aside. Matilda had originally been married to Henry, the Holy Roman Emperor, and she continued to be known as "Empress Matilda" for the rest of her life. She had no children by her first husband, and his death meant that she had to leave the Empire and return to England.

Her second marriage, arranged by her father Henry I of England, was designed to prevent the Duke of Anjou from being a pain in the neck. Unfortunately Matilda hated her new husband, and he wasn't exactly taken with her. Henry had to step in several times to prevent them from becoming completely estranged. In the end though they settled down enough to conceive several children, the eldest of whom was named Henry after his grandfather.

Henry's life was dominated by the war his parents waged against Matilda's cousin, Stephen, the new King of England. To this day historians argue over whether Stephen stole the throne from Matilda, or had been privately acknowledged as Henry I's heir. Either way, Matilda and Geoffrey were not about let an opportunity pass, and while Geoffrey focused on attacking strategic points in Normandy, Matilda travelled to England and waged war with the support of her illegitimate half-brother. "The Anarchy" as it became known, went on for years and decimated the English population. In the end a compromise would be reached, Stephen would reign as King, but his heir on his death would be Matilda's son Henry.

The Marriage

Of course, there was no guarantee that Henry really would be King on Stephen's death, at the time of the wedding it wasn't even much of a consideration. Stephen had sons of his own, and the English nobility may choose to support one of them instead. But Henry had learned a lot about successful warfare from his father, and was quickly gaining a reputation for being both brave and skillful. For a woman who had a Duchy to maintain, against enemies both inside and out, he was the obvious choice. Even as Eleanor was making her way home she had already decided to marry him.

The journey back was dangerous. In the medieval period a woman's consent to a marriage was considered a technicality rather than a necessity, and

there were several men who plotted to kidnap and marry her themselves, including Henry's brother Geoffrey, so they could claim Aquitaine. But through a combination of bravery and speed, Eleanor managed to evade the plotters and reach Aquitaine safely. Henry arrived soon after, and the hasty wedding took place at Poitiers.

Louis instantly reacted by gathering a force to invade Aquitaine. Henry collected his own troops, fully supported by his wife, and was quickly successful. Louis was humiliated twice over, not only was he beaten in the field of battle, but a year later Eleanor gave birth to a healthy baby boy, giving Henry the heir that Louis had always wanted from her, and proving once and for all that if there was a fertility problem then it certainly wasn't hers.

The enmity between Louis and Henry would continue for decades, and would see Louis successfully turn Henry's sons against him, and lead to Eleanor's imprisonment for supporting them over her husband. But at least on this day in 1152, she would have started to feel safe for the first time in weeks, if not months.

where she earned high praise for both her attitude and abilities. She was then parachuted in to France, where she met up with a local network. Her role was to oversee the groups finances and handle the division of weapons and supplies dropped by the Allies, but she was soon helping recruit new members, plan and oversee operations, and eventually came to lead over 7000 men. She claimed that her greatest moment was cycling a 300 mile round trip to get new wireless codes. She also killed a German sentry to prevent him raising the alarm, and shot a woman who was a German spy. In total her team killed around 1400 Germans, while suffering only 100 casualties.

where she earned high praise for both her attitude and abilities. She was then parachuted in to France, where she met up with a local network. Her role was to oversee the groups finances and handle the division of weapons and supplies dropped by the Allies, but she was soon helping recruit new members, plan and oversee operations, and eventually came to lead over 7000 men. She claimed that her greatest moment was cycling a 300 mile round trip to get new wireless codes. She also killed a German sentry to prevent him raising the alarm, and shot a woman who was a German spy. In total her team killed around 1400 Germans, while suffering only 100 casualties. Amelia, Alice Maud, James Henry and Kate Harris (my great-grandmother) all ahead of him, and Albert Edward, Harry and May still to follow over the years.

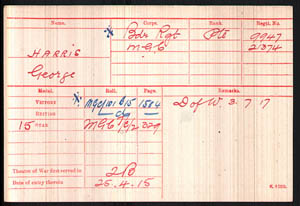

Amelia, Alice Maud, James Henry and Kate Harris (my great-grandmother) all ahead of him, and Albert Edward, Harry and May still to follow over the years. with them. They were promptly shipped back to the UK, and after a few months training were ready for deployment. But a lack of surviving service record hasn't stopped me from piecing together some of George's First World War history. His medal card shows that his first "theatre of war" was "2B", army shorthand for "Gallipoli", and that he first entered the war on 25th April 1915. On that date, 25

with them. They were promptly shipped back to the UK, and after a few months training were ready for deployment. But a lack of surviving service record hasn't stopped me from piecing together some of George's First World War history. His medal card shows that his first "theatre of war" was "2B", army shorthand for "Gallipoli", and that he first entered the war on 25th April 1915. On that date, 25

the Crown. However in the 1800s the Order was reformed as a chivalric order, with a new hospitaller organisation created thirty years later. The Order founded a series ambulances, aptly named "St John's Ambulance", which were designed to give members of the public lessons in first aid. The rapid industrialisation in Great Britain had not been accompanied by an increase in helping people work safely, and certain industries such as railways and mines often had high casualty rates. By offering first aid to workers and the public, it was hoped that someone who had been injured could be kept alive long enough to be taken to hospital or seen by the local doctor. It's from this that the modern St John's Ambulance organisation grew.

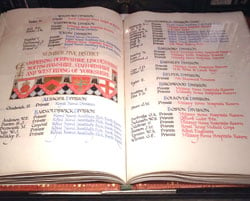

the Crown. However in the 1800s the Order was reformed as a chivalric order, with a new hospitaller organisation created thirty years later. The Order founded a series ambulances, aptly named "St John's Ambulance", which were designed to give members of the public lessons in first aid. The rapid industrialisation in Great Britain had not been accompanied by an increase in helping people work safely, and certain industries such as railways and mines often had high casualty rates. By offering first aid to workers and the public, it was hoped that someone who had been injured could be kept alive long enough to be taken to hospital or seen by the local doctor. It's from this that the modern St John's Ambulance organisation grew. "Roll of Honour" of members who died in the First World War, and more information about the first aid work of the modern St John's Ambulances, including it's work at the eye hospital in Jerusalem and training people in first aid in Africa.

"Roll of Honour" of members who died in the First World War, and more information about the first aid work of the modern St John's Ambulances, including it's work at the eye hospital in Jerusalem and training people in first aid in Africa. Isabella of Bourbon. Her mother died in 1465, leaving Charles with Mary as his only heir. The general view at the time was that a girl couldn't possibly rule, and therefore Charles decided to remarry. In 1468 Mary acquired a step-mother, Margaret of Burgundy, the sister of King Edward IV (and later, Richard III) of England. Margaret and Charles never had a child, but Mary became close to her step-mother, and it was Margaret who guided Mary's steps when tragedy struck again in 1477, when Charles died in the Battle of Nancy.

Isabella of Bourbon. Her mother died in 1465, leaving Charles with Mary as his only heir. The general view at the time was that a girl couldn't possibly rule, and therefore Charles decided to remarry. In 1468 Mary acquired a step-mother, Margaret of Burgundy, the sister of King Edward IV (and later, Richard III) of England. Margaret and Charles never had a child, but Mary became close to her step-mother, and it was Margaret who guided Mary's steps when tragedy struck again in 1477, when Charles died in the Battle of Nancy. new

new  includes Catherine's own letters, which were preserved as her belongings were auctioned off after her death to pay her debts, as well as sources from archives in France and Italy, and earlier scholarly work. She includes family trees, lists of the main historical figures, and maps of France and Italy so you can go back and refer to them if you get mixed up (useful for me as I kept forgetting where La Rochelle is).

includes Catherine's own letters, which were preserved as her belongings were auctioned off after her death to pay her debts, as well as sources from archives in France and Italy, and earlier scholarly work. She includes family trees, lists of the main historical figures, and maps of France and Italy so you can go back and refer to them if you get mixed up (useful for me as I kept forgetting where La Rochelle is). This was slowly being balanced off by the development of Unions. But for the men of Burradon, this was still a long way away. Instead they were supported in their efforts by a local newspaper, The Daily Chronicle. In particular they were keen to start a fund that would help the widows and orphans of men who died down the mine. Before the disaster the men were trying to come to an agreement with the coal company, each man would pay 2d a week in to the fund, they wanted the company to contribute a further 1d per man each week. However the coal company was reluctant to take part.

This was slowly being balanced off by the development of Unions. But for the men of Burradon, this was still a long way away. Instead they were supported in their efforts by a local newspaper, The Daily Chronicle. In particular they were keen to start a fund that would help the widows and orphans of men who died down the mine. Before the disaster the men were trying to come to an agreement with the coal company, each man would pay 2d a week in to the fund, they wanted the company to contribute a further 1d per man each week. However the coal company was reluctant to take part. I was eighteen, and I never got round to asking him if any of his family had been living in Burradon at the time. One of the deceased was a Francis Smith, and a Thomas Smith is listed as one of the survivors, but Smith is a very common surname and I can't prove if they were related to my grandfather's family at all.

I was eighteen, and I never got round to asking him if any of his family had been living in Burradon at the time. One of the deceased was a Francis Smith, and a Thomas Smith is listed as one of the survivors, but Smith is a very common surname and I can't prove if they were related to my grandfather's family at all. Edward was young, he couldn’t lead his troops in to battle against the French (a guaranteed way to gain some popularity) or marry a beautiful princess with a rich dowry (a wedding was also a good way to cheer the people). His regency council, who had been named in Henry’s will, were quick to get him crowned as it gave both him and them legitimacy. While the organisation may have been rushed, the coronation itself was still a splendid display of Tudor wealth.

Edward was young, he couldn’t lead his troops in to battle against the French (a guaranteed way to gain some popularity) or marry a beautiful princess with a rich dowry (a wedding was also a good way to cheer the people). His regency council, who had been named in Henry’s will, were quick to get him crowned as it gave both him and them legitimacy. While the organisation may have been rushed, the coronation itself was still a splendid display of Tudor wealth.